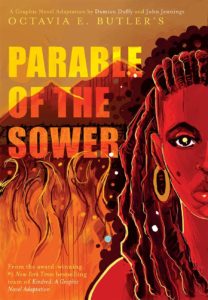

I just finished the graphic novel adaptation of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, and what in the entire FUCK?

A prophecy?

A warning?

…I’m listening.

But about a future among the stars, I have also told.

As you can see, it took me a while to get to Octavia Butler. When I read the words “science fiction,” I imagine the bleak, the boring, the unrelatable, the lasers and spaceships, and the inescapable despair. But as my husband and I wrote our first screenplay—a comedy, of course—we dreamed and outlined a universe that also included superheroes and aliens. By the time we finished our first draft of Caught Out There a month after we were married in 2018, there I was: a science fiction writer.

I’m a Black writer; that identity comes easily for me. But, science fiction? Yikes.

My co-writer is unmistakably the type. He’s well-versed on it all: comic books, action movies, guns and explosions and lasers and spaceships, the superior 80s cartoons, and the Sherman’s Showcase soundtrack (with a side of knowing all the lyrics to DMX and Ol’ Dirty Bastard songs). He even writes a superhero blog with other writers for Urban 30. I’m into local art and music, and a big chunk of my writing has been associated with the joy of shaking my butt at go-gos. I don’t feel like the science fiction type, but this constant perceiving of myself as an outsider to, well, everything, is likely the thing that makes me the type.

We’re primarily billing the movie as a romantic comedy, or, at least, a type of it, given our profound respect for the platonic love between our main characters and the hilarity that ensues. Besides, when I start talking aliens, I can feel half of my intended audience disconnect…just like I did all these years I’ve been hearing about Octavia Butler.

“Earthseed is all that spreads Earthlife to new earths.

The universe is Godseed.

Only we are Earthseed.

And the Destiny of Earthseed is to take root among the stars.”

– From EARTHSEED: THE BOOKS OF THE LIVING (Parable of the Sower, Butler, 1993)

I am floored. Catching my breath.

So, now I gotta connect dots. I’ve been reading Earthseed verses and being all, “What is happening to me?” for the last 24 hours.

Heartly, the Black woman protagonist in our movie, lives on Earth in the near-now-future and is seriously contemplating getting the hell up outta here. Not to die, but to go Out There! In Heartly’s Earth reality, the extraterrestrials who have taken Black human form have begun to invite those who are ready to see what’s Out There.

And yesterday, there I go discovering Earthseed. And not just Earthseed, but in Butler’s Parable of the Sower, all of the other things that feel too soon, too real, too probable to ignore.

What am I supposed to do with my thoughts and art now?

Keep going, obviously. But, shit, man.

My husband and I decided to make Caught Out There ourselves, independently. We are doing our best with what we have, along with help from crowdfunding and from selling the screenplay as an e-book. We shot our first three scenes earlier this year–the last one on March 12th, the day before our kids’ last day of in-person school. The pandemic has been a severe blow to production, but hey, maybe people will want to read a screenplay for fun in the meantime.

Wells confided to her diary, “I have firmly believed all along that the law was on our side and would, when we appealed to it, give us justice. I feel shorn of that belief and utterly discouraged, and just now, if it were possible, would gather my race in my arms and fly away with them.”

-From “Ida Taught Me” by Dr. Koritha Mitchell, Black Perspectives

More than a hundred years ago, IDA B. WELLS, the journalist, educator, and activist who risked her life to tell the Truth (yes, with a capital-ass T), was also dreaming of flying away with our people! I don’t know if she was imagining the cosmos, but the very idea of scooping us up and flying away strikes me just the same.

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, photo retrieved from US National Park Service https://www.nps.gov/people/idabwells.htm

And I haven’t even read HER stuff yet. She is on the ever-growing list of people and history I need to read in order to fully serve my purpose in my primary career. After the academic hazing that was a Ph.D. program, it has been a journey to return to a love of reading for my own fun and relaxation. Reading Black histories for my own general knowledge is just what I do.

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett wrote about lynching, though. My mind gotta be right.

My primary career identity is as a community psychologist. I specialize in professional development with groups of people from organizations, programs, colleges/universities, and businesses about their work with various communities. While learning my field in college and grad school, one thing that was most disappointing was the lack of historical context given when we were taught to diagnose, to create a program, to apply an approach, to interview, to research, to conclude, and to offer policy recommendations. The way I was taught, even if unintentionally, was as though Black people just fell out of the sky one day in the 1960s with much lower income and standardized test scores than the idealized white group, and that since the 1970s, psychologists have taken on the herculean task of finding out why.

With such out-of-context framings in education and at least 200 years of deliberate, systemic efforts to use mass media to negatively stereotype Black people, it’s no wonder that Black historical truths and Afrofuturistic ideas can be disorienting. As it has always been my own responsibility to learn my peoples’ histories, it has also become my responsibility to teach these histories. In doing so, I discovered that some people are taken aback by the horrors of American history—usually the ones who need to believe that this country has always been a good place and that they, personally, have no part in oppression. Others are shocked and angry that certain histories had not been taught to them in school.

At the same time, I can’t help but think of how Hollywood seems to release big-budget Black pain movies, or what some have called Black Trauma Porn, more often than big-budget movies (of literally any other kind) with majority-Black casts. I don’t have any data to back that up, just my confirmation bias bolstered by similar complaints on social media. Movies have offered versions of the histories we don’t learn in school, but Black people desire and deserve so much more than the fictionalized versions of our past and present pain. Black creators and fans have been calling attention to their Afrofuturistic faves for a long time, but widespread acceptance of such themes came through Black music and fashion far sooner than other mediums. We have gleefully gone Black to the Future through the work of Labelle, Grace Jones, TLC, Janet Jackson, Janelle Monae, and many more. Yeah, I named all women on purpose.

Labelle, photo retrieved from Philadelphia Music Alliance https://www.philadelphiamusicalliance.org/honoree.php?id=142

I am mulling over my recent exploration of Octavia Butler’s work (I also read Kindred two years ago when my 9th grader was assigned it) and my forthcoming dip into Ida B. Wells. It’s not that I was unfamiliar with these women and their work. I was scared. Stories that come through either of these women come with pain. A lived past and an imagined future can be rough on the mind.

That’s the point of the Parable of the Sower in the Bible. You can scatter those seeds, but they won’t take root and bear fruit everywhere.

Some shit, you gotta be ready for.

Rollercoasters, jumping off cliffs, swimming in more than five feet of water, psychedelic drugs, and other such thrills have never been my thing. Leaving the house, answering the phone, studying and sharing Black histories, writing Afrofutures, and speaking in front of large groups of people are the thrills I seek. Those last three are matters that necessitate coaxing people into attempting to understand something.

With my own work in speculative fiction, I need to use humor. Real life is wild enough—past and present—not to mention chaotic imagined Afrofutures. My goal is to escape, and to enjoy.

Aliens and superheroes make our screenplays science fiction, but I can feel myself distancing from the term in order to ensure that a broader Black audience feels safe enough to give the screenplay a read now, and to watch the movie when it is finished. It feels safer to call it a romantic comedy and let people discover the extraterrestrials later. I am reminded of the tightrope I walked promoting my book God Laughs, Too: Incidents in the Life of a Black Chick; the religious people were mortified, and I had to learn to market it to people who like weed, drinking, parties, cussin’, sex, AND God.

There’s a lot of ‘em.

For a couple of years now, I’ve been screenshotting and collecting tweets in which people mention wanting a spaceship to come and get them or wanting to get off this planet.

Again, there’s a lot of ‘em.

Did you hear? N.K. Jemisin’s Emergency Skin just won the 2020 Hugo Award for Best Novelette. I am cracking my neck and adding her work to my list.

The people been ready. As always, it’s up to me to get MY mind right.

My husband and I laugh a lot as we write, conceptualize, and make notes on the whiteboard in our shared basement office/parent cave. We have the sequel to Caught Out There outlined and another screenplay halfway finished. No aliens or superheroes in that one, but it exists in the same universe.

Pain and grief are already nearly constant in real life, so we focus on the fun in our multi-layered realm of hilarity, exploring the concept of something beyond Earth that serves an Afrofuture.

“But there’s always a lot to do before you get to go to heaven.”

-Lauren Oya Olamina, Parable of the Sower

~*~*~*~*